The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

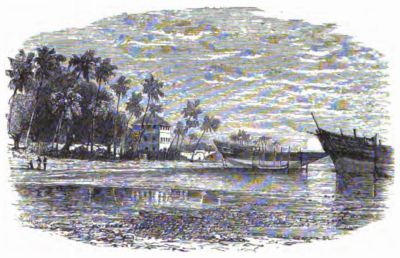

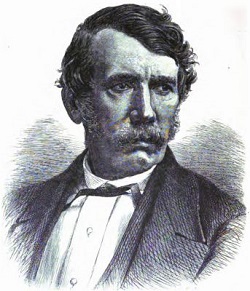

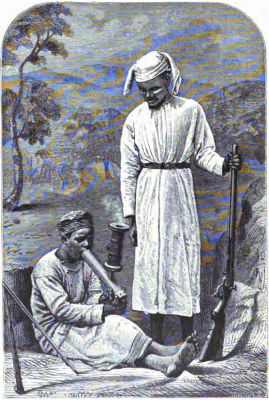

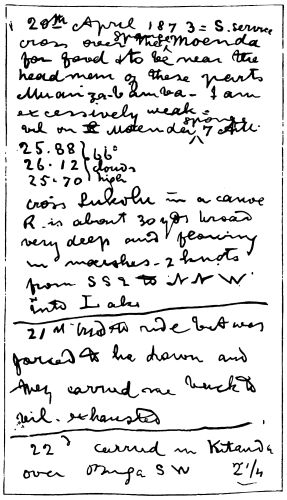

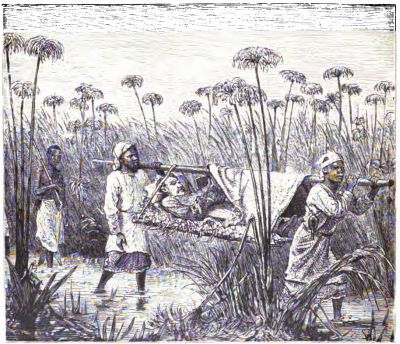

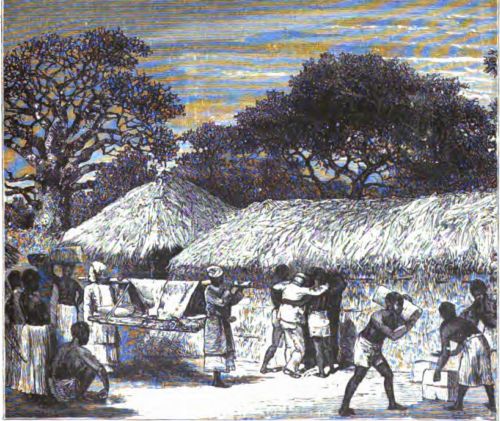

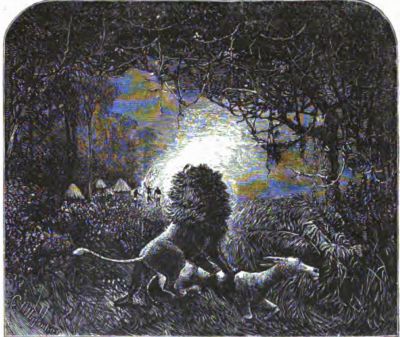

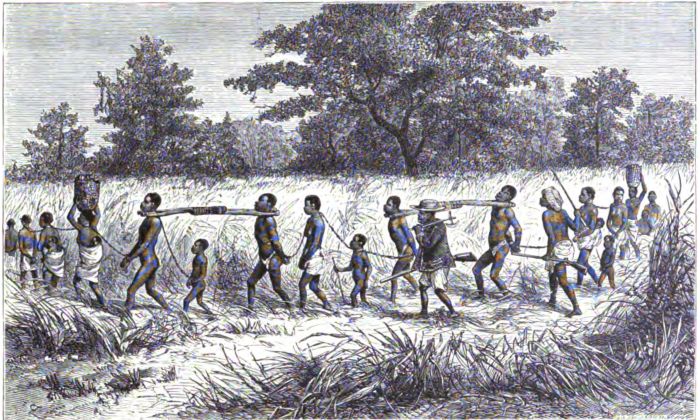

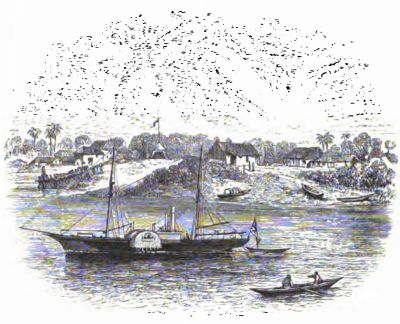

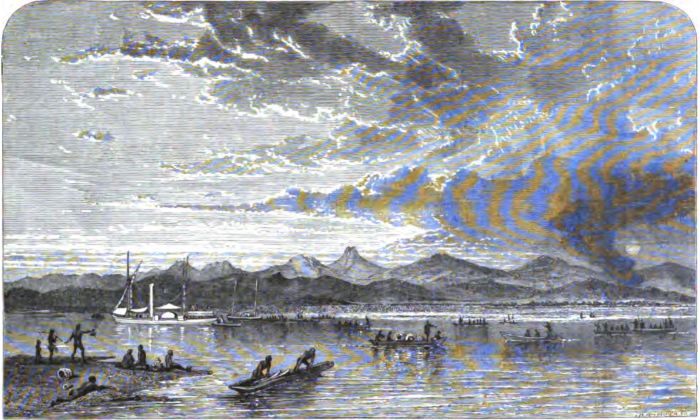

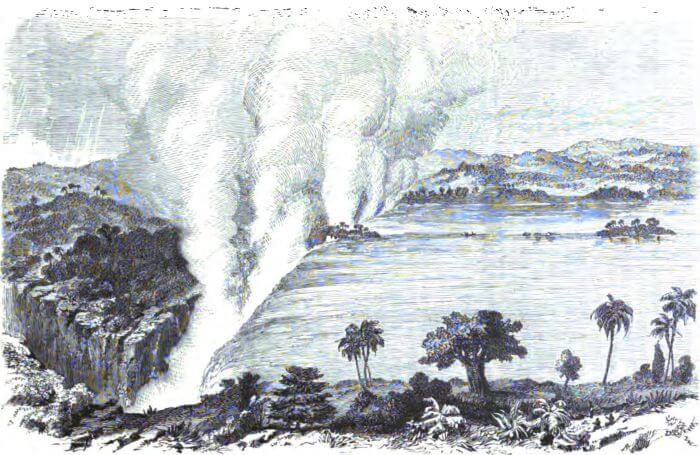

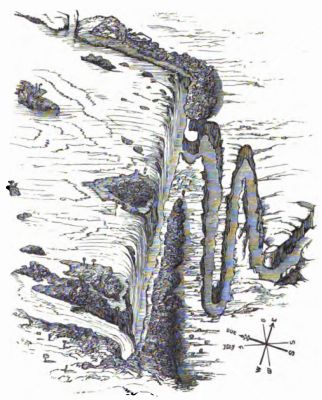

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Pictures

Activity 3: Observe the Modern Equivalent

Activity 4: Map the Chapter

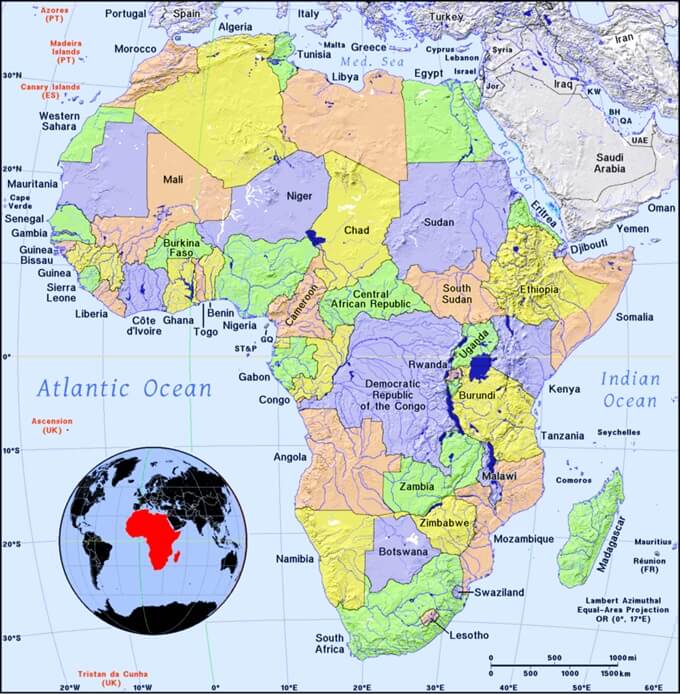

Victoria Falls is a waterfall located in southern Africa on the Zambezi river between the countries of Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Find the countries of Zambia and Zimbabwe on the map of Africa.

Activity 5: Map the Chapter on a Globe